(NOTE: According to caregivers familiar with his case, there is zero evidence linking Dale Cheney’s medical incident, described below, to the COVID-19 vaccine he received earlier in the day. He just happened to be at the vaccine clinic when the incident occurred.)

Thousands of Central Oregon seniors have gone through the switchbacking vaccine line at the Deschutes County Fair & Expo Center over the past several weeks.

“Most days, it’s pretty uneventful,” said Dr. Matthew Slater, a cardiothoracic surgeon with St. Charles and one of many physicians who have volunteered to provide medical staffing for the fairgrounds COVID-19 vaccine clinic. Their job, typically, is to keep an eye out for people having trouble standing or moving through the line, to answer questions prompted by a pre-shot screening process and to respond when a patient has a reaction to a vaccine.

“That’s 99.9% of what we do there,” Slater said, “and then the rest is true medical emergencies.”

Medical emergencies have been rare so far, but they’re certain to happen, given the sheer number of people expected to be vaccinated at the clinic over the next few months, said Bo Miller, St. Charles’ medical director of provider informatics.

“We want to vaccinate as many people in Central Oregon as possible in the clinic,” he said. “When you have thousands and thousands of people, many of them elderly or with pre-existing conditions, the probability of a serious medical event unrelated to the actual vaccine is very real. We accounted for that and have a system to handle emergencies, no matter how uncommon they are.”

To date, St. Charles has spent around $250,000 on the vaccine clinic, Miller said, stocking medical supplies, upgrading the WiFi, paying for interpretation services and incurring other expenses to ensure patients are as safe as possible during their visit.

“We want people to be confident they can come here, get their shot and go home, and we’re watching out for them every step of the way,” Miller said. “If something goes wrong, we’re as prepared for it as we can be.”

DALE’S STORY

Dale Cheney of Redmond was scheduled to get his second dose of COVID-19 vaccine at 8:30 a.m. on Feb. 18. But he was up and ready to go by 7 a.m.

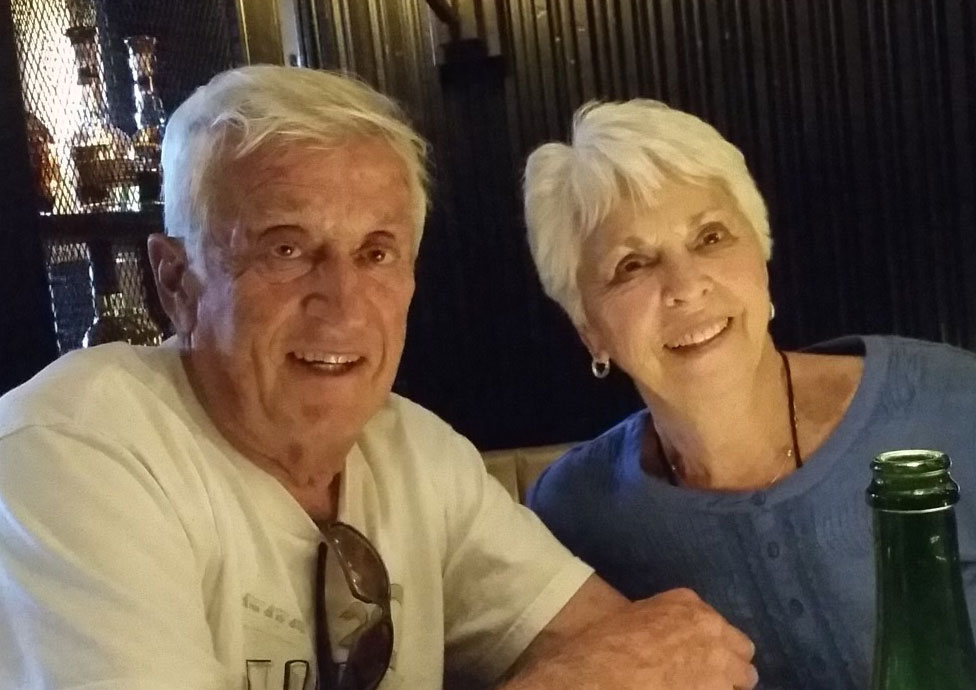

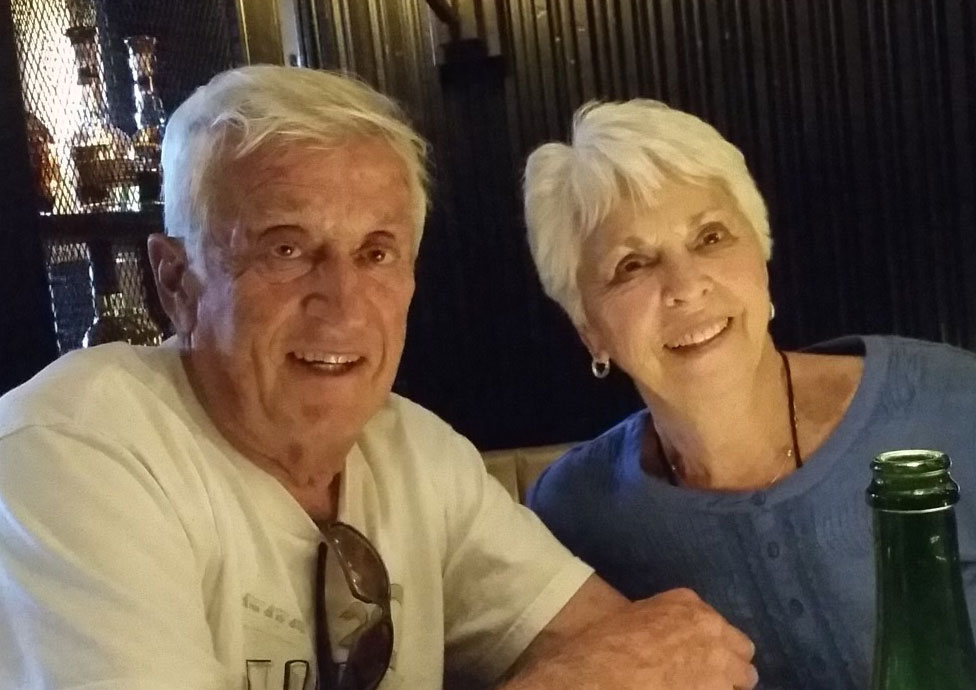

“I told him he should go ahead and go if he wanted to,” said Dale’s wife of 63 years, Judy. “So he left, and he had his cane with him because his back always bothers him if he has to stand for a while.”

Judy, 84, didn’t think anything of sending Dale to his appointment on his own. “He was in excellent health,” she said.

Dale, 86, arrived at the fairgrounds to find a line of about 50 people waiting to enter, Judy said, but a man near the front of the line saw his cane and invited him to jump in ahead of him. Once inside, Dale was escorted past the switchback section of the process and taken directly to a vaccination table, where he received his shot, she said.

From there, Dale walked to the respite room and took a seat to wait 15 minutes to make sure he didn’t have a reaction to the vaccine. After about five minutes, he looked up, Judy said, and made a mental note of how long he’d been there.

And that’s when Makena Forestell, a combat medic with the Oregon National Guard and a pediatric medical assistant at Mosaic Medical in Bend, heard Dale’s cane hit the linoleum floor.

“It drew our attention to him as he collapsed,” said Forestell, who was standing just a few dozen feet away. “We ran over to him, and when I saw other people initiating First Aid and blood all over his face, I went to grab gloves and gauze.”

Cheney had suffered a heart attack — unrelated to the vaccine he’d just received — and tumbled forward out of his chair, landing on the floor and breaking his nose. The first people to reach him were Forestell and Tiffani Soliz, a combat medic with the Guard and a medical assistant for Mosaic Medical in Redmond who, according to Forestell, “took charge of the situation immediately” by starting CPR and calling for an automated external defibrillator (AED) when she couldn’t get Cheney’s pulse. Soon, they were joined by paramedics from Redmond Fire & Rescue, as well as Slater, who immediately recognized Cheney’s affliction.

‘HE WAS DYING’

“I’ve seen a lot of dying people, unfortunately, in my career, and he was dying,” Slater said. “He was grey. He was struggling to breathe. He was clearly having what I thought was a cardiac event.”

The group worked to clear Dale’s airway and administered CPR while Forestell attached the AED to his body. After one shock and more CPR, a second shock — combined with a dose of epinephrine — brought Dale back to life, Slater said. He was then transferred to St. Charles Bend for further evaluation and treatment.

A week later, all involved were quick to credit others for the save. Soliz said a sheriff’s deputy did a good job of keeping onlookers away and helping to protect Dale’s privacy. Slater praised the “spectacular” work of the Guardsmen and the Redmond paramedics. Soliz also said the impromptu team worked incredibly well together. “I’ve seen established ER teams that didn’t work together as well as we did,” she said.

“Thankfully, this happened in a place surrounded by doctors, medics, paramedics, EMTs and nurses,” said Forestell. “We were able to get to him quickly and it worked out alright.”

For Judy, her husband’s good fortune started earlier in the day.

“The way it all came together — that he went an hour early, the man who called him to the front of the line — it all led to him being in that chair at that moment,” she said. “Had it been just a minute’s difference, he could’ve fallen while he was walking. He could’ve had it in the car. He could’ve died at home.”

THE SYSTEM WORKED

Besides staffing the clinic with the right people and positioning them effectively, Miller and a group of St. Charles caregivers worked diligently before the clinic opened to make sure the right equipment, the right medications and the right protocols are in place and ready for the most likely medical emergencies. They brought in a fleet of golf carts to transport mobility challenged people from the parking lot to the front door, and they placed wheelchairs strategically throughout the facility. They even closed half the bathrooms to give people less space to roam between their shot and the respite room.

Not all of those factors directly affected Dale Cheney’s incident, but it’s that kind of planning and attention to detail that put him in the right place at the right time and surrounded him with the resources that saved his life.

“It’s never a good day to have a heart attack, but if you’re going to do it, it’s best to do it in front of a system designed to rescue you,” Slater said. “The system is designed to give us the best chance of saving somebody, and this is evidence that it worked.”

EPILOGUE

Dale Cheney was discharged from the hospital a week after his heart attack and had a few days of feeling good at home, said Judy, his wife. But then he stopped eating and started losing strength, and on the first day of March, he went back to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with pneumonia.

He passed away late in the evening on March 5.

Judy is devastated, and she is also grateful to the people who cared for her husband that day at the fairgrounds. She’s thankful that their life-saving efforts gave her a couple more weeks to talk to Dale and take care of him.

She said she has asked God why He saved her husband only to take him a short time later, and she thinks she knows at least part of the answer.

“What happened to him that day was a miracle,” she said. “And we need to tell people about it to let them know that miracles do still happen.”